Rethinking Tech Capacity, Talent, and the Environment: Where Do We Go From Here?

This is a moment of change and intense ambiguity across the public sector; especially for the dozens of federal agencies tasked with stewarding our environment and protecting public health.

From disaster mitigation and response, to the wildfire crisis, clean energy, and public interest tech—thousands of federal employees have been fired or put on leave, and dozens of major initiatives eliminated. Leaders across organizations and sectors are trying to gauge impacts in real-time, but the tumult of recent weeks also recasts familiar questions about the government’s capacity to tackle big, complex environmental goals using better tools and data.

What’s already clear, though, is that federal workforce reductions to date will have reverberating effects on the ability of government at every level—and across its many partners—to deliver on environmental and natural resource goals with widespread support. After all, those who enter or stay in federal agencies in the months ahead will still make decisions that will shape the country’s ability to meet sprawling stewardship targets for decades to come.

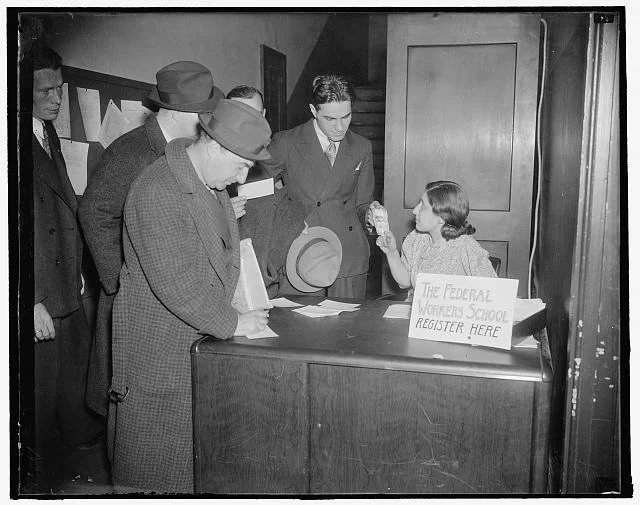

The Government Workers Union sponsors a “school” in the nation's capital focused on federal employees at the height of the New Deal. Nov. 30, 1937.

Source: Library of Congress.

At the heart of that challenge is not just the question of capacity lost, but also whether agencies had what they needed to succeed in the first place: the right people with the right skillsets, in the right roles, armed with the tools they need for the job.

Rethinking Talent and Tech Capacity.

For those concerned about the future of federal agencies or the civil service, it may be tempting to sideline that question amid the churn of the moment—but the honest answer is “no”...especially when it comes to the vital technical roles that underpin innovation in the public sector.

A EPIC, we call a more holistic approach to problem-solving inside government tech capacity. And in our experience, it's just as much about people—their skills and workforce needs—as it is about how and where they work, i.e., things like organizational mission, resources, and the many other process, policy, teaming, and data factors that shape their work. In essence, tech capacity is about how the government finds, hires, trains, and uses—but also how it empowers or inhibits—its technical workforce in the course of pursuing its missions.

Robert Fechner, first Director of the federal Civilian Conservation Corps, appoints its first enrollee, 22-year-old Elbert Jackson Lester, to the federal civil service rolls on March 3, 1937. Lester is flanked by Fred Morrell, Assistant Chief of Emergency Conservation Work for the Department of Agriculture (left), and Conrad Wirth (right), Assistant Director of the National Park Service. Source: Library of Congress.

Tech capacity is also where the noble but often unwieldy nature of those missions collides with the messy realities of culture, system silos, policy, and numerous data and technology barriers. The stakes of using good tech and data in (and across) agencies to do stewardship bigger, faster, and better are obviously existential today—but the capacity gaps that have long plagued public servants are widening, look increasingly hard to close. “On the ground,” that means decision-makers can’t effectively locate, monitor, protect, manage, or permit environmental assets or projects at scale, and our failure to track those assets, investments, and processes comprehensively—or to evaluate the constellation of impacts and user needs across programs, jurisdictions, and systems—also means leaders in and outside government can’t plan, mitigate, or build in the ways we need them to.

Compounding those gaps are the stark, but not inevitable, facts of public sector tech talent. Technology continues to outpace many agencies’ ability to find or use the best people and tools for the job; especially when it comes to vetting, buying, or building technology that actually meets user and mission needs. What’s more, and despite promising headway made by leaders in civic or public interest technology (PIT) and digital services in recent years, the skillsets agencies need are increasingly technical—and their workforce planning and hiring capabilities arguably less equipped than ever to compete in a dynamic labor market, or to survive the political headwinds we’re seeing play out daily. Talent and workforce capabilities may only form one “piece” of the tech capacity puzzle—but without it, all the other pieces can’t lock into place.

Where do we go from here?

For those trying to change that status quo, the shifting political landscape raises more questions than answers. Which is why we think now is the time to revisit the roles of tech talent and capacity, and to design new strategies around building the workforce we need to meet environmental goals in an uncertain future.

To that end, EPIC’s technology program is kicking-off a spring research sprint: in a series of semi-structured, off the record interviews, we’re surveying a wide cross-section of subject matter experts and public servants working to improve how government at every level sources, deploys, and retains a modern technology workforce—paying special attention to the policy, technical, and mission areas that impact environmental stewardship. To us, tech talent encompasses not only traditional technologists (e.g., software engineers), but also the many skillsets (designers, data workers, content strategists, and others) that foster user-centered tech and data use. Beyond the learning we plan to do alongside partners and experts, it’s also our intention to enliven, and better integrate, a network of organizations and leaders that share our mission—and then figure out how to mobilize their ideas in tackling urgent environmental goals.

Finally, a word about why we’re not doing this project. The last thing we want is to produce another well-intended report that essentially tells policymakers, NGOs, practitioners, or advocates what they already know. EPIC is part of a thriving ecosystem of civic tech, talent, data, and innovation-focused leaders with a common interest in technology for the public good; and many have been building field coherence and doing useful, talent-related research in this space for over a decade. Our hope is that by engaging a wide range of perspectives during this period of acute change—and across sectors and professional boundaries—we might gain fresh insight into barriers old and new, uncover hidden connections, and find case studies or collaborations to inform solutions going forward. We hope you’ll join us.

Does our vision resonate with you? Do you have experience or ideas around tech talent or capacity we need? Know someone we should interview?

We want to hear from you.