Why the "foreseeable future" matters

Two arctic species, two different outcomes

In March 2019, the State of Alaska petitioned to have the Arctic ring seal removed from the Endangered Species Act. Only seven years earlier, the NOAA Fisheries listed the species as "threatened" based on how climate change will reduce the sea ice and snow cover the species relies on. NOAA estimated this threat out to the year 2100, stating that it was able to reliably "foresee" that far into the future based on models of how global greenhouse gas levels would affect the Arctic environment.

In its petition, Alaska claims that NOAA's projections to 2100 were too speculative and that 2055 is the longest that "reliable predictions may be made regarding climate-related effects." To support this claim, Alaska cites the 2017 U.S. Fish and Wildlife decision not to list the Pacific walrus, which is also threatened by Arctic sea ice loss. There, the agency limited the foreseeable future to 2060, because "beyond 2060 the conclusions concerning the impacts of the effects of climate change on the Pacific walrus population are based on speculation, rather than reliable prediction."

Two mammal species face the same threats from climate change, but the outcomes under the ESA differ remarkably, partly because of how each agency interprets the foreseeable future. Adopt a shorter timeframe for the foreseeable future and threats far out into the future don't need to be considered, making listing less likely. Adopt an extended timeframe and those same threats factor into the listing decision. This is one way that the foreseeable future matters. As climate change continues to affect more species, how the two agencies interpret the foreseeable future will become only more important.

Major Changes to the Foreseeable Future?

In August 2019, the Trump administration finalized extensive changes to the regulations and policies for the ESA. One change was to codify into the regulations a definition of foreseeable future that's based on a 2009 Fish and Wildlife Service memo that explained the phrase and that both agencies have followed since then. The memo limits the foreseeable future to a timeframe over which predictions are "reliable." The Trump administration's codification is based on a "likely" standard, which the agencies explain means "more likely than not." Many commentators have already claimed that this definition will restrict the ability to list species under the ESA, especially those affected by climate change. We are skeptical of these predictions because the "more likely than not" standard is more permissive than those we've seen in a handful of ESA decisions on controversial species. But rather than speculate about the effects of this change, we'll use science to determine whether the foreseeable future will change. Continue reading to learn how.

Our Study on the Foreseeable Future

Using real-world data to understand change

Despite the importance of the foreseeable future concept, hardly anyone has evaluated how the Services have interpreted the phrase in practice. How often do the Services assign a timeframe to the foreseeable future? What is that timeframe and does it change over time? A 2009 study addressed these questions, but since then no one had continued the work.

If the definition of foreseeable future will change how this phrase is interpreted, the best way to understand that change is to compare foreseeable future analyses before and after the definition takes effect. That's what we're doing. We’ve located and analyzed all 420 ESA decisions from 2010 through July 2019 that interpreted the foreseeable future. With this baseline established, we'll track future decisions to determine whether the foreseeable future changes and, if so, by how much and why.

Click on the thumbnail image to the left to see our main findings on the foreseeable future.

Our findings to date

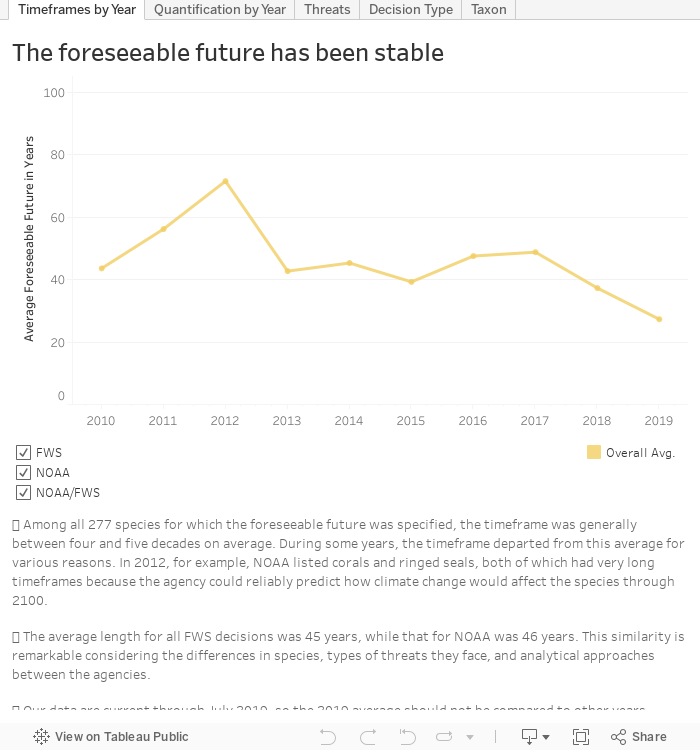

The five visualizations below summarize our main findings to date. Click on each tab to see the visualizations. Click on the check boxes to display/remove data layers.

We'll periodically update the visualizations below with our interpretation of the most recent foreseeable future decisions, and we plan to publish our comprehensive results in a journal soon.

Our Recommendations

We found several straightforward ways for the Services to improve how they apply the foreseeable future. In fact, NOAA has already been applying most of these recommendations in many of their ESA decisions.

Quantify the foreseeable future whenever possible. The Services are not legally required to specify the timeframe for the foreseeable future, but doing so usually improves public understanding of how the agencies decided on the timeframe. Further, many decisions we reviewed specified timeframes implicitly--we often had to read a decision several times to identify which timeframe corresponds to the foreseeable future. Both of these problems are easily fixable. Unclear decisions undermine the legitimacy of ESA decisions, encourage litigation, and build the case for reforms to the ESA that are overly broad.

Specify the maximum foreseeable future timeframe. Many ESA decisions specified the minimum timeframe for the foreseeable future rather than the maximum. The maximum, however, is almost always more informative than the minimum. For example, explaining that the foreseeable future is "at least" 10 years doesn't reveal how far the foreseeable future extends--and whether a species is still secure at the end of that timeframe. This is most problematic for decisions to delist a species and to not list one, because they assume that a species will be secure for the entire length of the foreseeable future.

Be consistent about climate change projections. One of the murkiest aspects of the decisions we reviewed pertained to how the Services determine the foreseeable future for climate change impacts. There are multiple scales at which the agencies can project these impacts. At the broadest scale, global greenhouse gas levels are well modeled and support reliable projections to the end of the century. But such extended projections become more difficult as scientists try to project how climate change will impact specific regions or locations in the world, such as the talus slopes of western Arkansas. Thus, the length of the foreseeable future is closely tied to how "downscaled" the Services require their climate change analysis to be. The challenge is that the agencies have not developed guidance on how they decide when to use global, regional, or local climate change predictions for any particular type of decision. Lack of consistency on this issue has led to litigation including over whether to list the wolverine in the Northern Rockies.

Develop national guidance on interpreting the foreseeable future. To ensure that the Services apply best practices to interpreting the foreseeable future, they should develop national guidance for these analyses. Recommendations like the ones we've offered should be part of the guidance, helping to ensure that the hundreds of biologists who draft listing decisions have standards to help them arrive at consistent and legally-defensible decisions.

Analyses and webpage by Jake Li and Angus McLean.