The Corps’ New e-Permitting - First Look at Current Functionality

With scant fanfare, the US Army Corps of Engineers entered the digital permitting age in January 31 2024, launching a version of its Regulatory Request System (RRS).

This is how the Corps describes RRS in its current state - with tools that are currently functional bolded (as of late February 2024):

“RRS, currently in a beta version, provides general information on the Regulatory Program and allows the public to submit pre-application meeting requests and jurisdictional determination requests. Additional capability is scheduled in Spring 2024. This added capability will allow users the ability to electronically submit individual and general permit applications and other necessary information, saving time and reducing the need for paper-based submissions. RRS will streamline the permit application process and underscores USACE commitment to modernizing our application process, meeting user expectations, and providing a transparent, straightforward process for the timely review of permit requests.”

In this blog, we’ll review what is functional right now on RRS (JDs, pre-app meeting request, and reporting violations), and the planned external user beta test of online permitting.

TLDR; my take is that this early functionality is indicating that the RRS will be mainly an online form and place to upload documents. The best advancements are 1) potential* time savings for Corps staff who will no longer have to manually enter information from permits into the Corps’ national permit database called ORM (which stands for the OMBIL Regulatory Module, and OMBIL stands for… well, who knows and it doesn’t matter), and 2) the collection of spatial data (project location, aquatic resources) that could be an invaluable resource to the public. The biggest miss is that there does not appear to be a placeholder for public-facing information about permits or many other advancements in permit transparency and timeline accountability, as we’ve seen in other online permitting examples.

*I say potential time savings, because some (all?) Corps Districts have ORM data upload sheets like this (link downloads an excel file).

IMPORTANT NOTE: While we’ve gone in and looked at the RRS’ functionalities below, we did not submit them. Don’t submit a request or JD unless you really mean it! The final step in a JD or request for a pre-app meeting is to sign and certify - among other things - that the information is correct and a person could face a big fine / prison time (!) for falsifying information (18 USC Section 1001). If you have logged into RRS and started one of the processes but don’t want to submit it, you can back out of the process and the RRS will automatically save the project as in progress. There is a ‘My Dashboard’ menu item on the top right navigation panel. If you click on this, there is an option cancel requests in progress that have not been submitted.

Here’s What the Online Jurisdictional Determination Process Looks Like

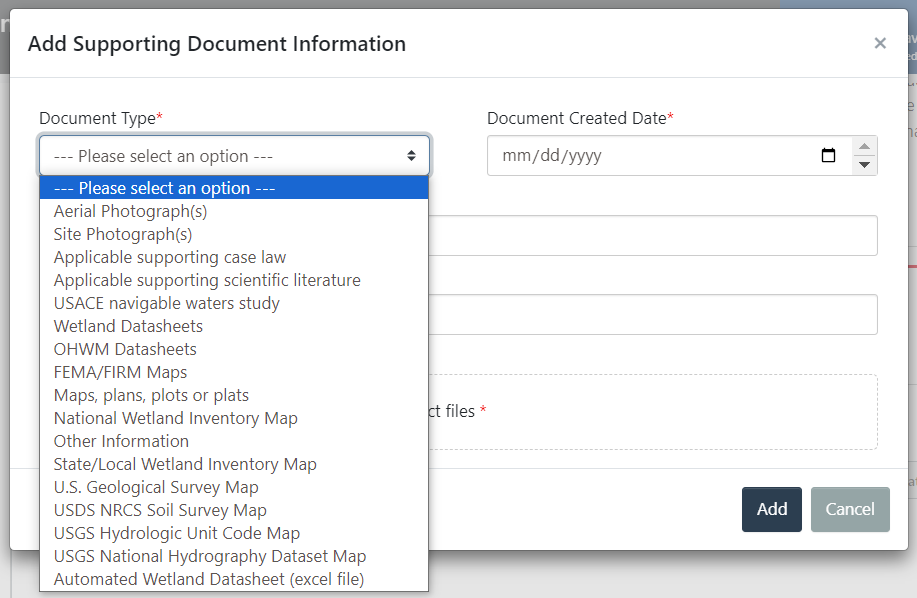

It’s easier to show rather than tell, so below is a video showing the steps involved in jurisdictional determination, along with a screenshot of the drop-down menu of supporting information that can be uploaded (skipped on the video). It was sped up to compress file size, so use the pause to look around at each step. Scroll below to see what I think are noteworthy functionalities.

Screenshot of menu of options of types of supporting documents that can be uploaded in the JD process (skipped in the video).

Noteworthy functionalities of the JD process in RSS:

The aquatic resource inventory step from 1:49 - 3:03, which includes a way to bulk upload a csv or geodatabase of the aquatic resources on the site. This includes:

WOTUS category of the type of aquatic resource (or exempted area) based on the current definition, which includes categories like: Traditional Navigable Water (TWN), adjacent wetland to a TWN, non-WOTUS tributary evaluated under (a)(3) and determined to not be a relatively permanent water with a continuous surface connection to [a TWN], exempt ditches, and more.

Hydrogeomorphic (HGM) wetland classifications, which includes depressional, estuarine fringed, lacustrine fringe, mineral soil flats, organic soil flats, riverine, and slope.

Cowardin code, which includes categories such as E1 subtidal estuarine, L2RS rocky shore littoral lacustrine, M2 intertidal marine, and many more.

The upload supporting information step (screenshot below video), includes ways to upload a variety of supporting information. Some of that information is using already-available datasets (NWI, soil survey map, etc.), while other information would be collected specific to the site (site photographs, wetland and ordinary high water mark datasheets, supporting scientific information).

All of this indicates that data will be collected by the Corps - public data (public once the permit is approved) that could be valuable for reuse. In particular, spatial labelled wetland delineation data could inform the National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) map and could be used to train an AI model to update wetland maps in areas not updated for 20+ years. Automated wetland determination datasheets - particularly those submitted as an excel spreadsheet (see available datasheets here and scroll down for a screenshot of the type of data collected in these sheets in the Midwest Data Form Version 2.0) - could be aggregated to a national dataset.

Here’s What the Pre-App Meeting Request Looks Like

Below is a video showing the steps in making a request for a pre-application meeting with the Corps. As the RRS notes, a pre-application meeting is “typically held prior to an applicant submitting a project application and are normally reserved for larger and more complex projects that require a standard individual permit.” There are many recommended documents / information to provide in this process including: a draft WOTUS delineation, draft project plans, draft alternative analysis, draft project purpose and need, draft avoidance / minimization / compensation statement, The video was sped up to compress file size, so use the pause to look around at each step. Note the only difference when choosing pre-application request type (standard permit, mitigation bank, etc.) is that ‘scoping request for environmental compliance’ asks for the date scoping comments are due.

As with the JD process, the pre-app meeting request process includes a collection of data / documentation. The upload supporting information step (2:54) includes: delineation of WOTUS, draft alternatives analysis, threatened / endangered species report, draft avoidance and minimization statement and / or conceptual compensatory mitigation plan, scoping letter, draft prospectus / conceptual mitigation plan, and other. These are examples of how this data could be re-used if collected in a standard format & associated with the unique ID of the project (/permit if ultimately approved):

Quantifying the amount of wetland and stream impacts avoided and minimized.

Endangered and threatened species on site could be provided to the US FWS.*

Known cultural or historical resource issues could be aggregated at a state or national level.*

*Note these two datatypes could be either buffered to protect specific location or could be flagged as information that cannot be provided to the public.

Beta-Testing Online Corps Permitting

The functionality above gives a good preview of at least some of the steps that could be in the wetland and stream permitting functionality, but we won’t know for sure until we see the version that will be released to a select group of users to beta-test in late February 2024. We were one of the lucky ones to make the list (out of 30 testers across the country), and we are planning to gather input from additional stakeholders. Our understanding is that the Corps wanted to create a beta version of RRS first, and gather feedback later. It’s a little concerning that the system didn’t originate from the needs of users (Corps permitting staff, external permittees and their consultants, community groups, non-profits, and academics) a la human centered design principles, but we’ll withhold judgement until we get to see it in action.

The Corps issues 3,000 individual permits and 35,000 general permit verifications annually, so getting an e-permitting system right has huge implications of time and headache for all involved.

In previous EPIC research, we identified the top bottlenecks in the US Army Corps of Engineers’ review process and highlighted dozens of solutions that could be implemented. At the top of my wishlist of improvements in the Corps’ permitting process is creating accountability through transparency and automated reporting, and adoption of e-permitting technology like Virginia’s Permitting Enhancement and Evaluation Platform (see EPIC’s case study: If You Can Track a Pizza, You Can Track a Permit). So far, there’s no indication of transparency of permit data (which is public information, but currently inaccessible without a FOIA request), and no indication that there will be automated reporting.

We will update this blog when we have been provided an opportunity to beta-test the system.

Until then, fingers crossed.

Reference Information

Screenshots of data collected in these sheets in the Midwest Data Form Version 2.0.

The Restoration Economy Center, housed in the national nonprofit Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC), aims to increase the scale and speed of high-quality, equitable restoration outcomes through policy change. Email becca[at]policyinnovation.org if interested in learning more, sign up for our newsletter, or consider supporting us!