United Kingdom’s Net Gain for Biodiversity Goals

Over the last decade, the European Union has studied, piloted, and then mandated new levels of protection and restoration for all biodiversity within member states, especially for actions funded with transfers from the EU budget. Under EU policy, and then on its own basis post-Brexit, the United Kingdom has gone even further, putting together one of Europe's most exceptional efforts to protect biodiversity alongside pragmatic policies to offset unavoidable damage with restoration and protection work elsewhere.

(This is Part II of four posts that detail the innovations happening across Europe in biodiversity policy and on the ground action, especially approaches that incentivize businesses, farmers and other parties to invest in the expansion of ecological conditions. Part I provided an overview. Part III will look at outcome payment or Pay for Success approaches to biodiversity recovery on farms, especially in Ireland. Part IV looks at voluntary corporate action to achieve no net loss or net gain for biodiversity with a focus on Sweden.)

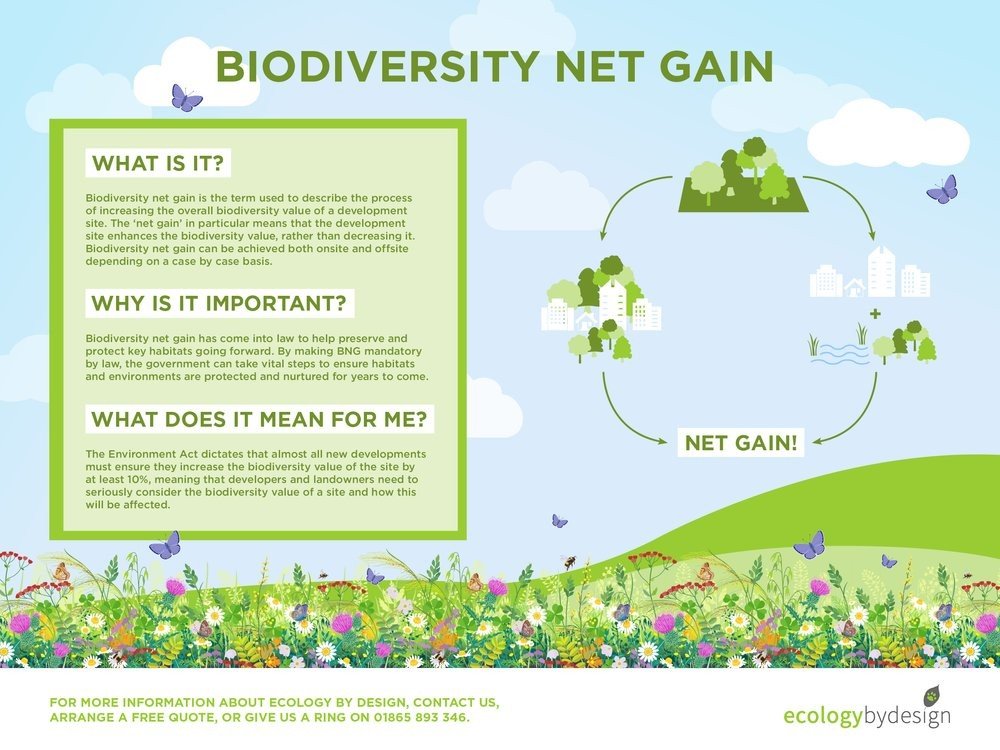

The Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act of 2006 created a broad duty to conserve biodiversity for national agencies and local government and private actions. The subsequent 2021 Environmental Act further elaborated the UK’s requirements, set a goal to achieve a net gain (of 10%) for biodiversity, and included procedural requirements for biodiversity net gain plans before construction of development projects can begin and policy to regulate supply of biodiversity offsets for harm that can't be avoided.

Subsequent regulation and policy development is still ongoing to implement the Environment Act, but it will depend on debit/crediting quantification tools that are already in a third iteration (called 'Metric 3.0') and will impose avoidance requirements and offset solutions across all terrestrial habitats by 2025. This is one of the boldest biodiversity offset policies on the planet.

Unfortunately, the election of Prime Minister Truss may lead to the reversal of this progress as well as related efforts to cap levels of nutrient pollution in major UK waterways and the country's homebuilder lobby is working hard to ensure that outcome.

Important aspects of UK policy that support biodiversity avoidance and offsetting (through private investment in a supply of offsets) include the following:

Gains and losses must be quantifiable;

Additionality is a clear requirement under policy (but documents around its calculation imply some differences);

Minimization and offset measures must be maintained for a minimum of 30 years, locked in through an ‘s106 agreement’ or a ‘conservation covenant’ and be registered in a national database (i.e. a register);

Restoration and protection projects that are completed in advance of impacts receive more generous crediting (but its unclear if the amount of time its required to be completed in advance is punitive to investment-based approaches);

Net gain components must be in addition to existing requirements and those requirements cannot be part of the crediting;

Like US Clean Water Act policy (but not Endangered Species Act policy), the UK is implementing the goal of “expanding and restoring habitats, not merely protecting the extent and condition of what is already there”; and

Development of a list of habitats that are irreplaceable and thus should be avoided.

The UK carried out a series of early pilot programs with local governments that volunteered to join the effort in the early 2010s and they have evaluated those pilots. The evaluation identifies a number of risks to biologically effective offsetting as well as the development of a private investment-backed supply of offsets, including the following:

Developers had significant flexibility to negotiate with the agency to lower the mitigation measures they would take. This may have been because these were voluntary pilots, but it speaks to a mindset within agencies that the mitigation plan is negotiable. This is likely to undermine advance investment in offsets and predictability and timelines for businesses to meet offset requirements.

Local governments favor on-site and nearby offset actions which will undermine the broader ‘service areas’ needed to make larger investment-backed banks work but also the ability to use the best science to site investments in nature in places that are likely to be most out of harm's way in coming decades.

Not a single (private) habitat bank was used during the pilot. The evaluation suggests that part of the reason might have been the short timeline for pilot projects to take shape (<3 years), but it was notable that developers preferred projects on government lands and parks where they would get political credit (i.e. ribbon cuttings) for their investments. Developers should not be getting credit like this and the added co-benefit of access to politicians and favorable media if government receives the offset funding could undermine larger regional banking efforts.

Additionality evaluation may fall far short of potential U.S policy standards. For example, under the pilot program, two local authorities secured funds from biodiversity offsetting to allow them to change management regimes and increase the biodiversity value of public lands (including grassland, parks and nature areas). Cuts in government funding meant that these areas no longer had a taxpayer-backed budget to support this work so it was considered acceptable to use offset funds for it. Allowing this under policy creates a perverse incentive that rewards local political leaders who defund public lands management and thereby make those lands eligible for developer offset fees.

The fact that “on-site measures were considered to be generally cheaper and simpler than off-site compensation” suggests that DEFRA’s credit quantification system over-credits actions that can easily be taken in highly developed landscapes as opposed to highly natural settings. Reviewing two of the available quantification case studies reinforces this view. Under DEFRA Metric 3.0, “native biodiversity hedgerows” are given the same biodiversity credit scores as “salt marshes and reedbeds.”

UK policies (its unclear to me if its in law or just in policy) define the mitigation hierarchy more narrowly than it is interpreted in the United States. In the UK there is a stronger emphasis on all avoidance and minimization happening first before offsetting. This contrasts with US requirements that all avoidance and minimization actions be ‘considered’ but not necessarily taken before offsetting is allowed. For example, comments about offsetting creating a validated route’ to get around all on-site avoidance and minimization and “offsetting as a last resort” in pilot program reviews highlights potential government staff resistance to offsetting. This likely results in more actions taking place within the site of development and in closer proximity to other development, as opposed to being centralized in the places that are most important for biodiversity or most efficient to produce restoration gains. This was typical of early years of US mitigation policies (and German ones) before experts finally accepted the logic that nature is probably more resilient to further harm if its far from shopping malls, apartment blocks, and mines than right next to it.

Crediting and debiting tools

DEFRA – the national agency implementing the net gain biodiversity policy has established metrics for calculation of harmful and beneficial impacts that produces a single score for habitat credits and a single score for linear habitat features (like streams and hedgerows). The current version of that metric is called Biodiversity Metric 3.0 and its use has been mandated across the country.

The DEFRA method appears to take a large number of subjective criteria, subjectively scored, and then combine them into a number. Because so many subjective criteria are combined, it can give the illusion that the system is not subjective, but I doubt that is the case. For example, some subjective variables have an enormous influence on credit and debit calculations like ‘condition of each watercourse’ for which an assignment of ‘good’ versus ‘moderate’ condition leads to a doubling of the credits assigned to the habitat. ‘Strategic significance of each watercourse’ as high, medium or low is another example.

Nonetheless, the criticism of this quantification tool captured in Bloomberg in June is likely off the mark. The story critiques the allowance under DEFRA methods for one type of habitat to be used to replace another, while missing that this was an intentional goal of the policy for the purpose of allowing gains in rare and special habitats to be used to offset harms to common and secure ones. We could argue about whether that is a good policy choice or not, but its not an unreasonable premise that we would make the same choice in the U.S., if given the option to replace damage to a common farm pond, for example, with restoration of a calcareous fen that could be full of rare plants.

One of the most useful ways to get a more practical assessment of how their system works and its business implications is to review the four example case studies that DEFRA has published for: river restoration (with grasslands impacts), residential development, new dock, pier, and terminal development, and laying cables to new offshore wind projects.

Each of these case studies show the tough choices you have to make extremely complex ecological systems something that you can transact on the timeline of development permitting decisions. However, they also show - because they are part of a high degree of transparency DEFRA is providing while working with local authorities and experts to build this system - how adaptable the quantification tools should be to new information over time. Information that will help make them more accurate and precise.

Modeled costs of offsite biodiversity banks versus onsite compensatory mitigation. Credit: Ecosystem Marketplace

The other thing that the criticism misses - as do most criticisms of offsets - that the alternative to allowing them isn't some fairy tale world where governments and their voters just say no to economically valuable projects. Instead, not allowing offsets typically results in projects moving forward without any attempt to replace damage. That has certainly been the norm in the U.S. even under all the environmental laws passed since the 1960s. A small number of projects get stopped. Most get modified so the damage they cause is reduced, but still move forward creating net harm for nature resources and the taxpayers and communities who own those resources. The brilliance of offset policies is that they finally ask for something more.

Terminology Differences between DEFRA and the US

Although the 'mitigation hierarchy' of avoidance, minimization and offsetting is relevant both in the UK and US, different uses of the same terms could be a cause of confusion. For example, ‘avoid’ means the same thing in both places. However, in the US the term ‘minimize’ is used but in the UK they seem to use ‘mitigate’ to mean efforts to reduce harm that cannot be avoided. In the US, 'compensatory mitigation' or 'offsetting' is used to refer to the third stage of the mitigation hierarchy, whereas in the UK 'compensate' appears to refer refer exclusively to offsite beneficial compensatory mitigation whereas onsite compensatory projects – even if new – would still count as mitigation (i.e. minimization).

A long way to go

The scope of the UK's new biodiversity mitigation policies is breathtaking, as is the speed with which they are being developed. Agencies implementing it must be under enormous pressure to give up. For example, imagine in the U.S, we didn't just have 1,500 species that triggered permit requirements in a relatively small fraction of the country, but tens of thousands of species in every corner of America that did so?

However, if DEFRA and local governments can work to ensure there is an adequate supply of offsets available - provided by private businesses or government - then there is a chance that they will be able to keep iteratively improving the system to focus on the nature outcomes policymakers prioritize, and restoration and protection gains that have easily-documented additionality and durability. Private efforts like those by consultants to help develop net gain plans and by investment-backed restoration businesses like Environment Bank to provide credible biodiversity offsets across the country suggest that the United Kingdom is already well on the way toward a system of regulations and incentives that will benefit a broader proportion of the country's biodiversity and prevent more declines of species than we have yet had the imagination to dream about in the U.S.

A growing network of consultants and planners offer technical skills to developers associated with net gain requirements.