Top 5 Changes in the New GRI Biodiversity Metric

Corporations voluntarily report on sustainability metrics like greenhouse gas emissions; diversity, equity, and inclusion; and biodiversity. The Global Reporting Initiative’s (GRI) metrics are one of the most commonly used sustainability metrics, used by over 10,000 companies annually around the globe.

GRI recently released a ‘consultation draft’ of new biodiversity metrics.

Under the circa 2016 GRI biodiversity metric, a company had to disclose whether their operations were in or near a protected area like a national park or other area of high biodiversity, the kind of direct and indirect impact they had and on species, the species’ IUCN Red List status (indicator of extinction risk), and the species’ protection status (e.g., Threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act). A company also had to report the area of habitats they protected.

The new metric dives much deeper. A company now has to identify the most significant impacts of their own operations AND their suppliers’ operations on biodiversity, and the depth of what the company has to consider and report on has significantly increased. Additionally, new concepts like the mitigation hierarchy, ecosystem services, and access and benefit-sharing are introduced. Here are the big changes we think matter most:

Top 5 Changes in the New* GRI Biodiversity Metric

*This is a proposed metric. The final is expected to be released in Q3 of 2023. All quotes below are from the GRI’s proposed metric unless otherwise noted.

1. Supply Chain Impacts on Biodiversity. Greenhouse gas emissions metrics consider not just direct impacts but ‘Scope 2’ and ‘Scope 3’ emissions (ie., emissions from electricity used, and emissions from indirect activities like shipping products and employee commuting emissions, respectively). Biodiversity reporting is headed in the same direction. Companies must consider not only their own direct impacts, but the significant biodiversity impacts of their supply chain. ‘Significant impacts’ is a newly introduced term and the metric requires companies to explain how they came to identify these. The new metric also includes a submetric (#304-6) requiring companies to describe company biodiversity policies and goals and report on progress.

2. The Biggest Drivers of Biodiversity Loss Are Front and Center, and the Mitigation Hierarchy is Introduced. In this new metric, standardizes and probably makes it easier to report on impacts by asking for information on all the direct drivers of biodiversity change identified by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES): climate change, invasive species, land use change, overexploitation of resources, and pollution. Companies are also expected to describe how they avoid, minimize, restore, and offset the ‘significant impacts’ they identified. This sequence of avoid, minimize, restore, offset is called the ‘mitigation hierarchy’ and is found in many natural resource regulations and policies such as US regulations relating to impacts to wetlands and streams. The mitigation hierarchy is applied per usual to direct impacts to species, but also to the major drivers of biodiversity loss. The latter might look like “taking actions to eradicate invasive alien species.”

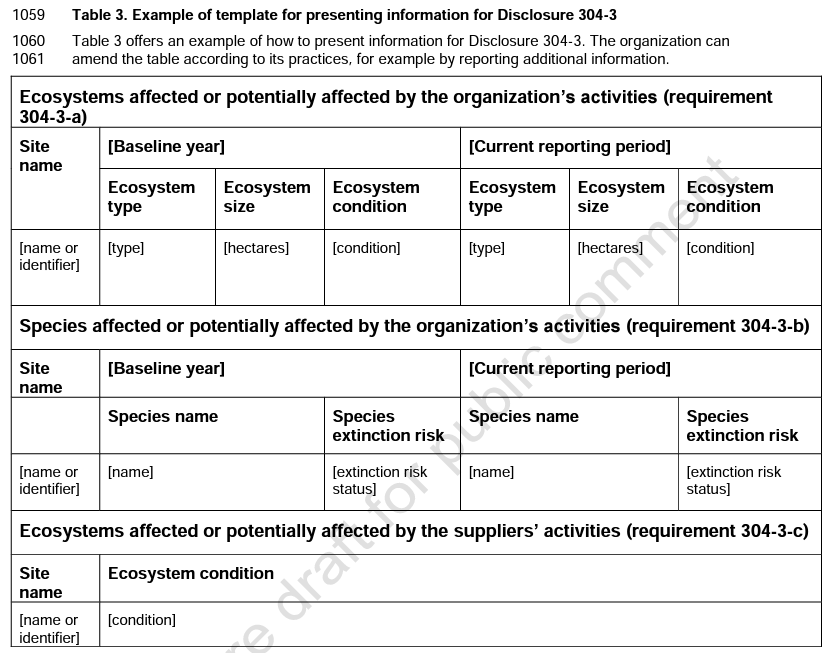

3. Companies Are Now Required to Measure Baseline and Current Biodiversity. Size and condition, species name and extinction risk are required for sites identified with significant impacts. This is the first time I have seen a focus on the condition of biodiversity in the metric. This could move the metric from being a coarse proxy of biodiversity to an on-the-ground, measured indicator.

An example given in the GRI consultation draft on how to report on baseline condition and changes in current reporting year.

4. Ecosystem Services Are Considered in the Biodiversity Metric. Ecosystem services are the goods and services that we get from nature (think: clean water, flood mitigation, aesthetic value, crops). The term has gone out of fashion in favor of ‘natural capital’ and ‘green infrastructure.’ By any name, the concept has been woven into previous metrics (biodiversity, rights of indigenous people, land and resource rights) but it has never been called out for its own reporting (sub-metric - #304-4). A company is required to identify “the significant ecosystem services and beneficiaries that are or could be affected by the organization’s [and supplier’s] activities” for each site previously identified with a significant impact on biodiversity.

5. Access and Benefit-Sharing of Genetic Resources Moves from the Convention on Biological Diversity to Corporate Sustainability. The metric notes that “Fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources is one of the three objectives of the Convention on Biological Diversity.” Companies that access or use genetic resources have to report on how they are following national requirements, and have to describe how they are sharing monetary and non-monetary benefits with communities (including indigenous peoples).

Biodiversity has always been a step behind greenhouse gas emissions in how much attention it gets. For example, 75% of companies report on carbon targets, but <50% report on biodiversity. But there is a lot of momentum in the international community, for example with companies making commitments to net gain of biodiversity. The IPBES updated their global biodiversity and ecosystem service assessment in the last few years, and the Convention on Biological Diversity just held its once-every-10 years Conference of Parties in Montreal. Developments in the international sphere are woven throughout the new GRI biodiversity metric. There is a lot more detail in the GRI draft consultation, but just from the 5 points above, I think it’s clear that this is a major change in biodiversity reporting. Beyond that, the biodiversity metric will pressure companies to better identify, avoid, minimize, and offset their impacts.

These are all positive changes that are critical if we are going to get to a future where biodiversity loss has been stabilized

The Restoration Economy Center, housed in the national nonprofit Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC), aims to increase the scale and speed of high-quality, equitable restoration outcomes through policy change. Email becca@policyinnovation.org if interested in learning more, or consider supporting us!