The Worst Trump-Era ESA Changes are Gone

The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) just released a set of final rules amending the Endangered Species Act (ESA) Section 7 and Section 4 - including 4(d).* The new rules remove all of the controversial Trump era changes to the ESA. Even though this may feel like Administration vs Administration, these changes are common sense changes to align text with the intent of the law.

We also support additional changes that won’t make the big headlines:

Section 7 changes

The specific inclusion of measures that offset the impact of incidental take

Adding the mitigation hierarchy into Reasonable and Prudent Measures (RPMs)

Allowing ~offsite mitigation (aka RPMs outside the action area)

Section 4(d) changes

The inclusion of federally recognized Tribes in §17.31(b)(1) and §17.71(b)(1) that will allow Tribes to take threatened wildlife or plants without a permit for the actions noted (aiding a sick, injured, or orphaned specimen; or disposing a dead specimen; etc).

*Cheat sheet:

Section 7 - the part that covers ‘permitting’ when the project has some connection to Federal funding or permitting. This is a big portion of permitting under the ESA, the other part is Section 10 when a project has no Federal connection.

Section 4 - covers the procedures and criteria used for listing, reclassifying, and delisting species and designating critical habitat.

Section 4(d) - relates to protections for threatened species.

Read on for more.

For background, the Trump administration in 2019 promulgated rules that changed the ESA for better and for worse. EPIC analyzed these changes carefully (hat tip: Ya-Wei Li and Tim Male) and found that some changes would result in no or very minor alterations to ESA practice, some should improve conservation, some changes would depend on how the agency implemented them, and yes, some of the changes could undermine conservation efforts.

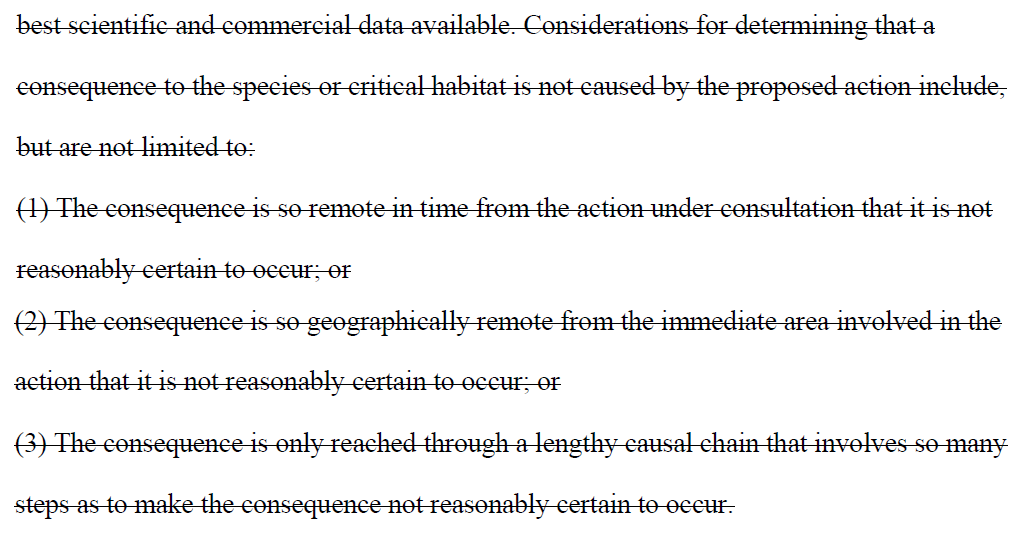

The most controversial changes that were implemented in the Trump era 2019 ESA changes were: 1. Publishing the economic impacts of listing decisions, 2. removing the 4(d) “blanket rule” (which in a nutshell automatically extended endangered-level protections to threatened species), 3. Limiting the designation of unoccupied critical habitat, 4. Removing climate change from what might be considered the “foreseeable future.”

The new rules remove all of these controversial Trump era changes

Red text are additions and strikethroughs are removals, based on changes from the 2019 version of the ESA.

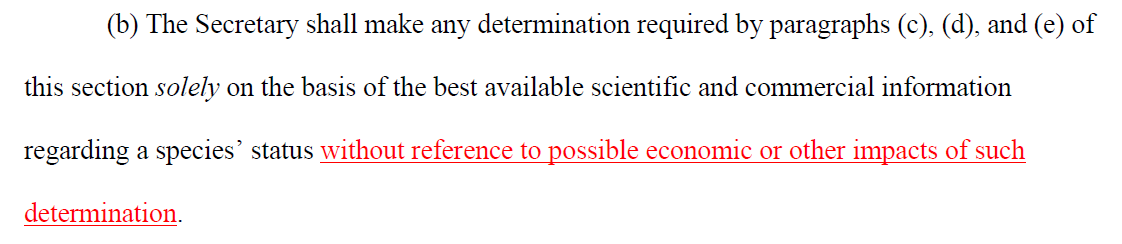

1 There’s no more taking economic or other impacts into account when considering whether to list a species or not

2 - The blanket rule is back

3 - Unoccupied areas can be designated as critical habitat

4 - Climate change is no longer off the table

Lesser-Known Changes That We Like

We are pleased to see that all of the changes we applauded in our comment letters made it in and the one critique we made didn’t make it in!

Section 7 changes

In a nutshell, these are our top three off-the-radar changes:

It allows offsets! The proposed rule now officially recognizes offsetting the impact of incidental take as a reasonable and prudent measure (RPM)

It doesn’t have to be onsite, which is good because doing small postage-stamp mitigation does not usually create the most optimal ecological outcomes.

There is a mitigation hierarchy. “Priority should be given to developing reasonable and prudent measures and terms and conditions that avoid or reduce the amount or extent of incidental taking anticipated to occur within the action area.“

For additional detail, see our comment letter for Section 7.

Section 4(d) changes

The inclusion of federally recognized Tribes in §17.31(b)(1) and §17.71(b)(1) that will allow Tribes to take threatened wildlife or plants without a permit for the actions noted (aiding a sick, injured, or orphaned specimen; or disposing a dead specimen; etc). As previous EPIC research has noted, “By definition, tribes are sovereign nations with the right to self-govern within their own territories” (Black Bird and Male, 2022). This should extend to how a tribe is treated in the ESA, and we support the Services’ effort to do so. Additionally, this is a great example of ‘cutting green tape’ for Tribal management of natural resources. Further, the report notes “a major cause of low tribal participation…is the absence of federal mitigation policies that appropriately consider tribes’ status as sovereign nations and various special circumstances derived from that status that need to be addressed.”

We are glad the USFWS decided not to include language that they were considering, which predicated giving Tribes an exemption with a requirement to have a “Service-approved cooperative agreement,” which we thought was an inappropriate stipulation. We are glad to see the Service decided not to include this language.

For additional detail, see our comment letter for Section 4(d).

The Restoration Economy Center, housed in the national nonprofit Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC), aims to increase the scale and speed of high-quality, equitable restoration outcomes through policy change. Email becca[at]policyinnovation.org if interested in learning more, sign up for our newsletter, or consider supporting us!