New Research: Bottlenecks and Solutions to Accelerate Conservation Bank Approvals in California

California is known for its strict environmental laws, which is understandable as the state hosts an amazing diversity of ecoregions and incredibly special places for species and humans alike. It’s strange, though, to see California’s environmental laws turn in on themselves and make beneficial restoration and conservation projects harder to approve. Did you know that an 800-mile pipeline across the state of Alaska requires less permits than a watershed restoration project in California? Alaska LNG: 15 permits; Elk River Recovery Program: 16. Ouch.

While efforts at Cutting Green Tape have made in-roads on reducing restoration project approval times, the time savings have not made it to the realm of conservation banking for state-listed species and habitats in California. The regulatory process of establishing a conservation bank for state-listed species in California is hindered by inefficiencies and regulatory ‘green tape,’ resulting in delays beyond the state-mandated deadline of 270 days (SB 1148).

Conservation banking is a niche term indicating restoration and/or conservation of species and habitat completed for compliance under a species protection law. The federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) both prohibit harm to species (technically called ‘take’) but provide a permitting pathway for projects that may unintentionally harm a species while carrying out an otherwise lawful activity.

“We could do 10x more restoration if CDFW stuck to their timelines” -Anonymous interviewee

Both ESA and CESA steer projects to avoid, minimize, and then mitigate impacts to species. Mitigation can occur either by the project proponent (called permittee responsible mitigation, or PRM) who generally restores and/or protects species habitat after an impact occurs, or mitigation can be created in advance through conservation banks that provide a credit that can be used to fulfill regulatory requirements. Conservation banks create mitigation in-advance of impacts and have been recognized in state and federal policies as a preferred alternative to 'postage stamp' offset projects (CDFW 1995, USACE 2008, USFWS 2023).

In the US, California has the longest history and largest volume of conservation banks. One might think that depth of experience would create efficiencies over time, but for conservation banks approved by the California Department of Fish and Game, the opposite is true.

At right is the percent of deadlines missed from the last five reports on conservation banking provided to the California state legislature

The Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) launched a research effort to investigate what speeds and slows conservation bank approval timelines, and what ecological and economic consequences come from delayed processes. This effort supports Governor Newsom’s 2020 Cutting Green Tape Executive Order, which aims to “increase the pace and scale of environmental restoration and land management efforts by streamlining the State’s process to approve and facilitate these projects.” EPIC analyzed ‘timestamp’ data of the approval process for a sample of 12 CDFW conservation banks and compared this to alternate data. EPIC also conducted 13 informational interviews with restoration providers and buyers. Researchers were unable to conduct informational interviews with CDFW staff due to conflicting priorities of staff, but CDFW was able to provide input in the form of one collective response to three key questions. Nine Regional Banking Coordinators from the seven CDFW Regions were involved in preparing the response and we appreciate the feedback.

Caveat: due to the differing methods of information-gathering as well as timing (CDFW input was provided the week prior to the publication date), the report has much more nuance and detail from the perspective of conservation bank sponsors and buyers as opposed to CDFW staff.

Is the Approval Process Meeting the 270-Day Timeline?

EPIC discovered that CDFW does not have a way to evaluate its own timeline based on the ‘timestamp’ data it records. This is problematic. Currently, the review time that CDFW is responsible for cannot be disaggregated from the time spent on the process by all actors including CDFW, the sponsor, the interagency review team, and external agencies.

The average total timeline from a sample of CDFW data is 761 days. This average, however, is much lower than alternate data sources. The average timeline from US Army Corps of Engineers timeline data on joint Clean Water Act/state species banks in California is 1,337 days. A survey of seven California CDFW bank sponsors found an even higher average total timeline banks approved by CDFW: 1,740 days. This alternative data indicates that CDFW data may underestimate the total approval timeline by as much as half.

Conservation bank sponsors and credit buyers also identified environmental and economic consequences of delayed approval timelines. If bank credits are unavailable, permittees must create their own mitigation, which means there is a temporal loss of the benefits of restoration and conservation, sometimes for years after the impact occurs.

The full scale of outstanding mitigation obligations in California is unknown and “could be one of the biggest conservation failures in the state in this decade” -Anonymous interviewee

High-quality habitat is lost because landowners get a better offer while an application is stalled out in the approval process. There are also economic consequences: permittees and staff spend 10-20x more time on one-off mitigation projects; the financial cost of supporting consultants and lawyers gets passed on to consumers and taxpayers; and delays mean it is hard to get beneficial projects like renewable energy approved.

What Are the Bottlenecks?

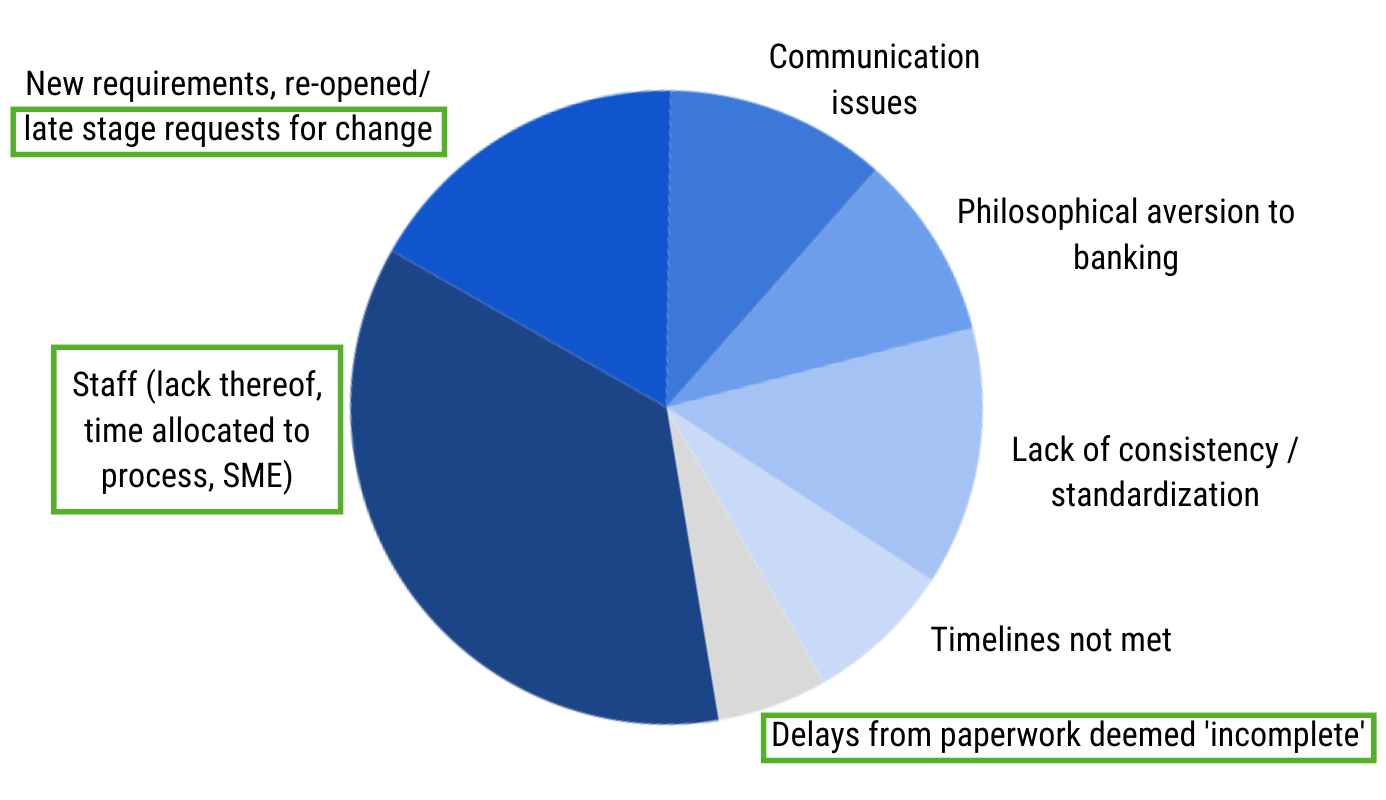

Restoration providers and conservation bank credit buyers were asked for their 'top 3' bottlenecks. The graphic shows the top responses. Similarities with CDFW input are highlighted in green.

There are ecological and economic consequences of delays. Interviewees indicated that if bank credits are unavailable, permittees must create their own mitigation, which means there is a temporal loss of the benefits of restoration and conservation, sometimes for years after the impact occurs. High-quality habitat is lost because landowners get a better offer while an application is stalled out in the approval process.

In terms of economic consequences: permittees and staff spend 10-20x more time on one-off mitigation projects; the financial cost of supporting consultants and lawyers gets passed on to consumers and taxpayers; and delays mean it is hard to get beneficial projects like renewable energy approved.

Solutions to Accelerate Conservation Bank Approvals

1. Address data issues and develop a meaningful way to track and report on performance on meeting the 270-day deadline in the annual report to the legislature. CDFW should refine data entry during the bank agreement review period so that CDFW review time can be disaggregated from time spent on the process by CDFW, the sponsor, the interagency review team, and potentially external agencies. This should enable evaluation of the 270-day deadline, which should be reported annually.

2. Prioritize conservation bank approval reviews and create accountability for sticking to the timeframe. Leadership keeping staff accountable to timelines along with having more champions of conservation banking were seen as means to improve accountability. Holding IRT members accountable for their review deadlines is another option to improve accountability to timelines.

3. Hire and retain staff dedicated to conservation bank approval reviews. Many interviewees experienced 2-5 different CDFW project managers over the timeframe of their bank approvals. Turnover and lack of sufficient staffing create an inefficient start-and-stop review process, compounding issues with timelines. This is also a top CDFW recommendation.

4. Identify opportunities to limit the addition of new requirements and re-opened or late-stage requests for change in the approval process. Interviewees hoped that CDFW (and IRT) staff could focus on requests within the agency’s authority, and requests that meaningfully added value to the species to reduce time and resources spent on non-essential activities. CDFW could also emphasize clauses in the banking agreement that reduce risk so that reviews are not striving for perfection / zero-risk. CDFW also had a preference for addressing concerns earlier in the process.

5. Both CDFW and sponsors want to keep templates , but sponsors would like increased objectivity in templates to improve standardization and consistency in the review process. CDFW creates templates and other guidance so that sponsors can have some predictability that adherence will lead to a faster approval process. They are not currently experiencing this. CDFW could also allow a bank agreement to stay ‘grandfathered’ in whatever version was current at the time the prospectus was submitted.

6. Apply and expand California’s Cutting Green Tape opportunities to the conservation banking review process. Although projects that create restoration for compliance purposes are eligible, banks have not benefited to date.

When asked what would CDFW not want to change, the response was the following:

Elimination of the IRT process.

Elimination of the banking program templates.

The level of review to ensure a successful project which may include assistance from species experts, legal review, and real estate package review.

Project scrutiny prior to establishment.

Where Do We Go from Here?

This report is intended to be a jumping off point for adaptive management of the approval process. As Governor Newsom expressed in his Executive Order on Cutting Green Tape, the point is to “increase the pace and scale of environmental restoration and land management efforts by streamlining the State’s process to approve and facilitate these projects.” Interviews with CDFW staff &/or dialogue between CDFW staff and stakeholders could provide additional insight and highlight the best opportunities for change. An analysis of the full approval timeline dataset is another potential follow-on step.

California Isn’t the Only Place We’re Looking At

At EPIC, we think it’s just not right that up to ⅓ of a restoration project’s funding is spent on permitting. We also think it’s a shame that the US public could lose out on $9.8 billion in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act [IIJA] tagged for restoration because the projects might not get approved before the ‘use-it or lose-it’ funds run out in 2026. We need money to go to Nature, not paperwork.

To that end, we’ve analyzed U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) data to see if timelines on Clean Water Act wetland and stream mitigation banks were meeting the federally mandated approval time limit of 225 days, and found the average project took 1.5x longer than required “on the regulator’s desk.” The full timeline for project approval - including back and forth between the Corps and applicants - takes over 1,000 days on average (the longest project took over 12 years!). Just like we did in California, we conducted informational interviews with wetland and stream mitigation bank sponsors to identify bottlenecks and opportunities to streamline the review process (coming very soon!). We’re also collecting examples of policies, programs and case studies of streamlining restoration permitting and ‘Pay for Success’ environmental programs. The database is a work in progress, but will be officially launched later this month.

Love our work? Join our newsletter or consider supporting us!